After the World Wars, many ideas were put forward on how the international community could live together peacefully. As a matter of fact, the League of Nations emerged with such an idea, but could not prevent the second great war due to the deficiencies in its structure. Afterwards, the United Nations was structured. In many massacres and genocides experienced today, it has been understood that this institution is ineffective in essence. When evaluated over a wide geography from Rwanda to Bosnia, from Arakan to Xinjiang, the thesis that the UN has not been able to fulfil its mission is indeed true.

Another structure established with a similar motivation is the African Union, from which great expectations are expected in the regional context. In this article, we will try to get to know the Union a little more precisely. After analysing its structure, we will focus on whether it has been able to fulfil its mission.

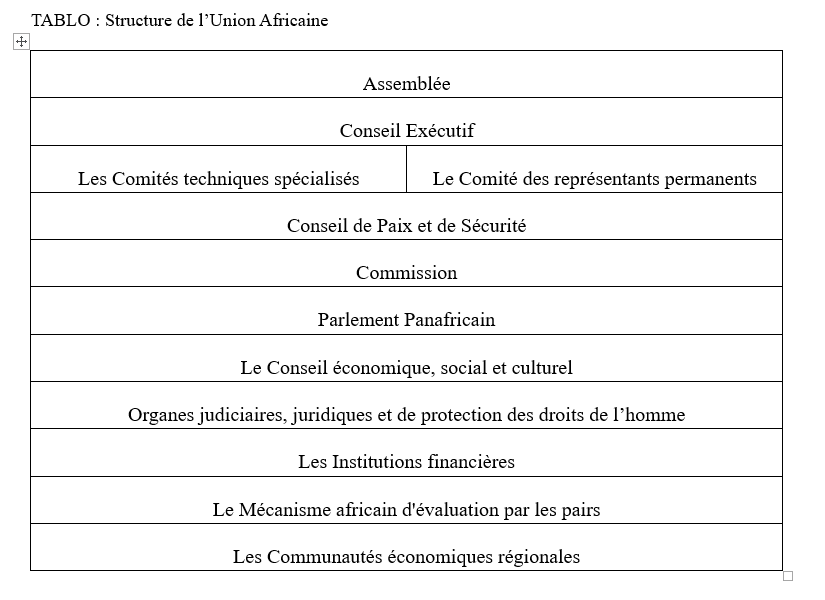

Establishment and Structure of the African Union

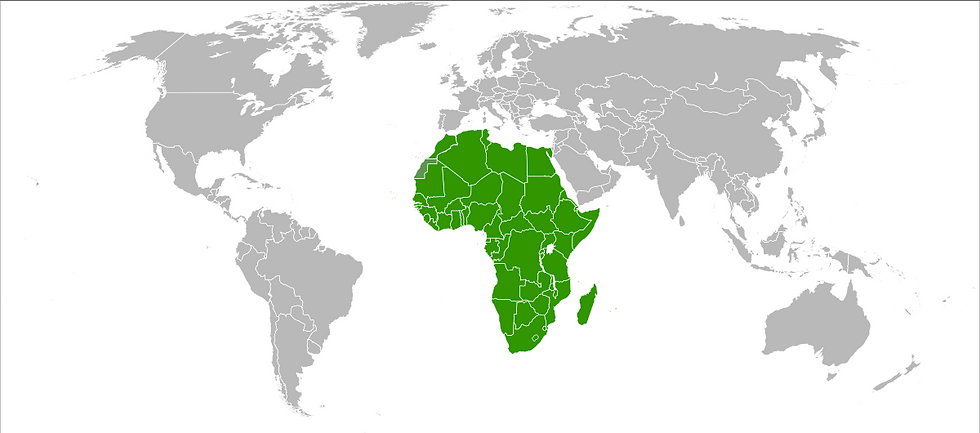

The African Union (AU) was officially established in 2002, replacing the Organisation of African Unity (OAU), which was previously established in a similar structure and aimed to represent Africa as a unified structure in the international arena. The goal of these institutions, which were established with objectives such as ending discrimination against the continent, promoting the idea of a united Africa, and achieving peace across the continent, is to represent all the countries of the continent. It represents the members of 55 different countries with its headquarters in Addis Ababa, the capital of Ethiopia.

The Union is compared to the European Union in many respects. Like the EU, the African Union has its own constitutional law. Adopted in 2001 in Togo, it sets out the objectives of the Union as representing Pan-African ideas, integration, human rights, peace and democracy throughout Africa.

As an intergovernmental institution, the African Union derives its authority, resources, and ultimately its power from its member states. Its forward-looking plans and programs are also determined by the member states and the bodies they elect. Despite this, the agendas of regional unions like ECOWAS are sometimes considered more important than those of the African Union, leading to the perception that the Union is not sufficiently strong. As this idea has become more widespread recently, many countries are calling on the African Union to reform its structure.

The Assembly is the top policy-making and decision-making body of the African Union. It brings together all African heads of state and meets at least once a year. It agrees on the policies and priorities of the African Union and monitors the implementation of policies and decisions.

The Executive Council meets in ordinary session at least twice a year and is composed of ministers of all member states (usually foreign ministers, but in some cases other ministries). The member state that chairs the Assembly also chairs the Executive Council and serves for one year. The Council is responsible for preparing the agenda for the Assembly's consideration. It also promotes co-operation and co-ordination with other African institutions and Africa's partners.

The African Union Commission (AUC) has an operational function. It plays a central role in the day-to-day management of the African Union, including the tasks assigned by the Assembly and the Executive Council.

The role of the Commission is to assist member states in implementing the programmes and policies of the African Union. Commission members are elected every four years and their positions are renewable once.

Is the Union Successful?

The Union has policies for Africa in many areas. It is controversial how many of these policies, ranging from trade to conflicts, are successful. Especially in the recent period, the increasing armed violence and conflicts across the continent have questioned the peacekeeping and security function of the Union.

In 2016, the Lusaka Roadmap was adopted to end conflicts across the continent. The document outlined 54 practical steps to be taken. Focusing on political, economic, social, environmental and legal issues, it was hoped to end conflicts by 2020. The map, which proposed a wide range of solutions, from ensuring sufficient funding for the deployment of a specialised peacekeeping force in Africa to preventing rebels and their supporters from accessing weapons, has failed.

At the time of the Declaration's publication, Africa was characterised by high levels of conflict. State and non-state actors in Africa fought around 630 armed conflicts between 1990 and 2015. Conflicts led by non-state actors account for more than 75 per cent of global conflicts.

In addition to its ineffectiveness in conflicts in many parts of the continent, the African Union's attitude towards coups is also questioned. For example, the fact that the Union, which did not object strongly to the coups in Egypt and Zimbabwe, took a clearer stance against the coup in Sudan has opened the debate on the existence of different standards. Egypt's membership, which was suspended due to a coup but later reinstated, contrasts with the situation in Zimbabwe, where no sanctions were imposed. Meanwhile, Sudan's membership remains suspended due to a coup.

The ineffectiveness of the Union has once again become evident in the events in Libya. This ineffectiveness has two consequences. One is that more foreign fighters are coming to Africa than in any other conflict zone, and the other is that countries are renting their bases to foreign powers in order to gain economic benefits.

It is a great risk for the independence of the continent for foreign actors to settle in the continent by renting bases and to control the routes favourable to their interests. Some countries, which receive million dollar incomes from the USA, China or other powers, jeopardise their independence for the sake of economic interests.

Despite all the risks, the African Union should reconsider its Constitutional Law to address the principles that limit the ability of member states to intervene in conflicts on their territory. This should lay the groundwork for establishing solid legislation, policies, institutions and mechanisms for long-term stability in such countries. It should go beyond condemnations of conflicts or coups d'états and should be on the ground.

In many parts of Africa, especially in the war against terrorism, governments seek the assistance of foreign powers and call the armed forces of other countries to their territory. The African Union is often left out or excluded in this system based on bilateral agreements. It is a disappointment that this large organisation, which is relatively better off economically and socially, has turned into such a weak and neglected actor in terms of security. It is not possible for this structure, which is influenced and modelled on the functioning of the European Union in many areas, to take Europe as an example in terms of armed forces. The African reality, which cannot be read through examples such as Europol, is quite different from European theories of non-conflict and peace. In all of the rebellions, border conflicts and civil unrest, the process that turns into armed action is not resolved through dialogue as in Europe, but again through military means. In such an environment, it is not realistic to believe that problems will be solved with European optimism.

The reality that elections are conducted under conflict in many regions, and that in some countries, the losers resort to weapons, exceeds the limits of an idealistic perspective for a solution.

Although the Union's former principle of non-intervention has now been transformed into indifference, the big gap between theory and reality on the ground persists. The most important thing that needs to be done is to put the intervention force that has been targeted so far on a solid footing and then to reduce the sphere of intervention of foreign powers on the continent in the medium term. The solution to a problem in Mali should be designed in Addis Ababa, not in Paris, and the problem in Madagascar should be solved without travelling outside the continent. The African Union emphasizes that prosperity cannot be achieved unless conflicts on the continent are halted, and this is a very accurate observation.

However, the African Union's sole duty should not be limited to making observations; it must also become a part of the solution. It is clear that a more independent and active union would also stand firm against neocolonial ideas on the continent. In doing so, the Union should of course benefit from other examples in the world, but it should be restructured by taking into account its own dynamics.

Comments